There Is A Light that Never Goes Out

In a valley formed by the Huallaga River lies a temperate land located on the eastern slopes of the central Andes of Peru: Huánuco. A little more than seventy years ago, in that land of mountains and starry skies at almost 2,000 meters above sea level, Juan Nájera was born. A multifaceted musician by profession, he did not always have the privilege of being able to dedicate his life to music. For almost ten years he ran a family hardware store in Huánuco and then a mechanic shop on La Marina Avenue in Lima. He was also a truck driver. A decade of military dictatorships in Latin America made the artist’s path very hard in the region, and Peru was no exception. Nájera was only nineteen when his first son was born. He had to make a living and the possibilities for entrepreneurship were slim. But if we go back in history, Juan Nájera was, first and foremost, a boy who dreamed of becoming a musician. Later, he was a boy who made it.

Juan Nájera has been passionate about music since school. His father, Alejandro Nájera, played guitar at home but never wanted to teach him for fear that he would go down "the wrong path", as his son would recall many decades later. Juan did nothing forbidden: he learned to play the guitar but had to teach himself. Because he wanted more agility in his fingers, he practiced day and night until he began to master the songs of Los Destellos and Los Beta 5, emblematic cumbia bands of the time. In high school he met Chony Rozales, who accompanied him on drums in school performances, and thus his dream of creating a band came closer to becoming a reality.

From the age of fourteen, Nájera was part of the Peña Artística Huanuqueña and was later invited to sing and play in another peña called Ondas del Huallaga, which led to his first tour of Tingo Maria, in the Peruvian jungle. Juan Alvarado, a friend of Chony's, was the third member and played the güiro. The two traveled together to Lima in 1969 to buy musical instruments in a store on Larco Avenue, in the well-known district of Miraflores, where the Pacific Ocean breezes blow. Money was a problem, but they were able to solve it quickly: Nájera received a loan from his father, who had already resigned himself to his son's musical devotion, and was able to buy three guitars; Arturo had saved some money from his job cleaning cars and bought a small sound system; Chony invested in a drum kit. They had already met Roberto Caldas, who would become the rhythm guitarist, and Peter Arce, the bass player. After long hours on the bus that would take them back home to Huanuco, they were greeted by the other band members waiting for them on the road. Happy and excited, they knew that this was just the beginning. The only thing left to do was to start playing.

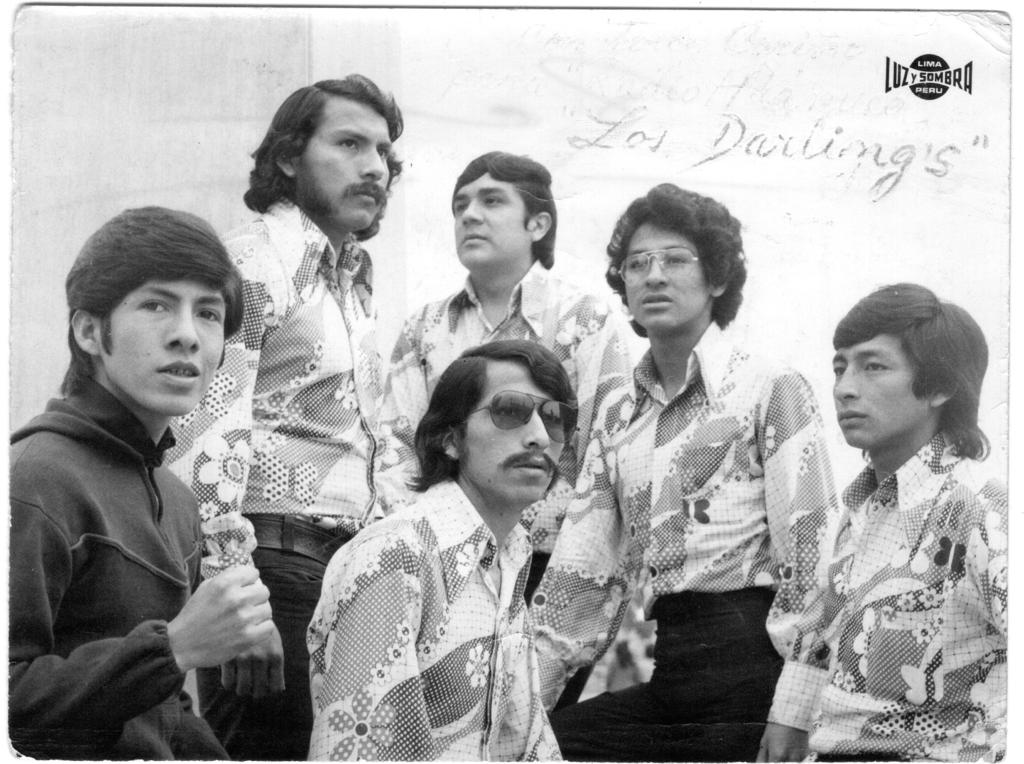

At first they were going to call themselves Los Darling Friends, but they thought it would not have a good commercial hook. So they decided to call themselves Los Darlings de Huánuco. The year after their trip to Lima they started working as entertainers at parties, and soon after, in 1971, they had a stroke of luck: in one of those weekend performances they were heard by the great Rulo Barrueto. Barrueto was not only an artist manager, but also the director of the group Orquesta Tropical La Sensación. He had the right contacts to get contracts and gigs. Coincidentally, Barrueto had disbanded his orchestra, which meant that not only did he have the time, as well as the interest, to represent Los Darlings, but he also had better quality instruments than them. Thus, an agreement had to be reached. Before long, Los Darlings had a manager and new instruments with which to begin writing their own songs.

They wasted no time. That year they recorded three 45 RPM records, which included tracks such as Corazón mañoso, El preso número 9, Pequeña flor, A los filos de un cuchillo and Marihuana. All the songs were recorded for the legendary Rey Record, a small boutique label born in the late 1960s that released 45 RPM gems and was run by Luis Lock Loli, a man who was a tailor and made custom suits for the presidents of Peru.

After having played covers of different bands they knew, the leap to play their own compositions earned them great recognition in Huanuco. It was time for them to conquer Lima, the capital. Although the band continued to play, disagreements with their manager led to a definitive separation in 1973. The termination of that contract also meant having to return the instruments they had grown accustomed to. This breakup took its toll on the whole band.

Juan Nájera was called to be the lead guitarist of Los Tigres de Tingo María, another well-known band from the jungle. He only lasted six months with them. Najera missed his town, his friends and colleagues. When he finally returned to Huanuco, his bandmates were waiting for him. They still believed they could do great things together, and they were not wrong. With that idea in mind, they once again traveled to Lima to buy instruments. In Huanuco there was no possibility of finding stores of the quality of the stores in the capital. So they scraped together some money, bought bus tickets and set out on the trip. Nájera and his father arrived in Lima, bought a professional sound system and returned. This time, there was no money for more.

Since it was impossible to rent a rehearsal space, these were held at Juan's house, who by necessity had also become the band's manager. Time and comings and goings brought changes: Carlos Lu, a friend from the neighborhood, replaced Peter Arce on bass, and Richard Galarza became the new rhythm guitarist. At that time they were playing Carlos Santana covers, but Nájera proposed to migrate towards Caribbean rhythms. It was a disagreement over their musical tastes that ended up driving them apart. For defending his ideas, Nájera was left alone. However, his solitude did not last long. It was not difficult to find other young enthusiasts who wanted to play. Oswaldo Galarza and Juan Casqui were summoned to play rhythm guitar and bass, respectively.

The only vacancy left was that of drummer. They usually summoned the great Coco Lagos, a sixteen-year-old kid who played with them in different private parties. But he still had a lot to learn. "He hit the drums too much, so I gave him some bongos to practice. Every day he would go to my house to rehearse, as if he was in school. One day, a drummer we had hired to play at a quinceañera party failed and I called Coco," recalls Nájera. After finding a permanent drummer, all they needed was a singer. And so came Jorge Daza, who at the age of seventeen was already singing tropical music. The band was complete, and the change of genre was the springboard to the capital.

Juan Nájera and Jorge Daza traveled alone to Lima to knock on doors and get shows for the band. They arrived at a venue called El Rinconcito Huanuqueño and asked to speak to the owner. After a long wait, the manager came out and, before they could finish their sentence, told them that they were not looking for a band to play. None of the previous ones had worked out and they had no interest in hiring them. Nájera did not give up and told the owner to listen to them and that he would not charge for the performance. The owner, wary, agreed. He had nothing to lose. At that point, the two band members hurried to a pay phone to call their colleagues who had stayed in Huánuco. Sometimes lies bring opportunities, and with that in mind, Juan told the others that he had gotten a contract and that they had to get to Lima as soon as possible because they had an appointment to play.

Two days later, the band was already rehearsing in the capital. The performance was on Saturday. But it was not just any gig. It was the most important one, the future of the band depended on it. Los Darlings could not have done better. The applause and ovations convinced the owner of El Rinconcito Huanuqueño to offer them a six-month contract, which was later renewed for years. In the capital they were also highly acclaimed in venues such as the Salsódromo Puerto Rico, located in the jirón Quilca, in downtown Lima, in Do Re Mi, on Colonial Avenue, in the Police Recreation Center and in various places where cumbia was played at that time. On occasions they shared the stage with cumbia bands such as Los Diablos Rojos, Los Girasoles and Los Destellos. Although their past songs were cumbia, Los Darlings de Huánuco played mostly salsa versions. "Salsa was more complicated for the musicians, it was a challenge for us. The most striking thing was that we played salsa with strings, with guitar and percussion. No other tropical group did it that way," explains Nájera.

From 1975 to 1980 they played at El Rinconcito Huanuqueño in the afternoons. On their nights off, they tried their luck in other venues in the city and its surroundings. In 1980, due to family problems, Nájera had to leave the band and return to his homeland. There he opened a hardware store where he worked for nine years. Music had been relegated to leisure time at home with friends and family. The band dispersed. Jorge Daza left with Carlos Nomura's orchestra. Coco Giles became an announcer for a salsa program on Radiomar Plus, and also worked as a program presenter on national television. Juan Casqui and Oswaldo Galarza immersed themselves in Lima's informal commerce. And Pocho, the tumba player, went to Venezuela to play in an orchestra.

After returning to Lima with his entire family in 1989 due to the insecurity in Huánuco, and dedicating himself to commercial work in a mechanical workshop, Nájera worked in the transportation sector. It was with the turn of the millennium when he returned to music.

Los Darlings de Huánuco managed to cross borders, not only in the capital of Peru, but also abroad. There are many collectors and music lovers around the world who seek and appreciate their songs, musical gems that have toured different latitudes and have managed to position this band from the Peruvian countryside in the most remote places on the planet. In a country characterized by its centralism, where opportunities in the countryside are much scarcer than in the capital, where the foreigner is greeted with more warmth than the local, and where getting ahead, especially in the musical field, implies an extraordinary effort, Los Darlings de Huánuco managed to take their sound to where they never thought it would be possible. From the Andes to the skyscrapers, from the heart of Huánuco to the immensity of other continents.

Ailen Pérez B.