Lucha Reyes, el cantar enferma

When she died, Lucha Reyes' voice had already reached unusual heights; like a curling wave, it had invaded the air at full speed until reaching the skies. It was 1973, and the “Morena de Oro del Perú”, the black diva who sang criollo waltzes and shone in luxury marquees, was 37 years old when her heart stopped on a timely morning: October 31, Criollo Song Day, her day. The streets of downtown Lima, crowded with religious devotees —who, like her, had dressed up in purple to attend the procession of the Señor de los Milagros that day—, went from sublime euphoria to the most intimate and fraternal mourning: not only had they just lost a woman whose vocal cords were thought to be truly made of gold; also 'La Reyes', like them, had emerged from the bowels of the alleys of working-class neighborhoods of the capital, had had the world and a social order against her and yet, being a woman, black, poor and harassed by sickness and violence, had managed to roar from the impossible to not be forgotten, to be loved, and had succeeded.

Her "ease of awakening passions in the public", as keyboardist César Silva remembers in the documentary "Lucha Reyes, Carta al Cielo" by Javier Ponce, earned her the love of time. Although Lucha Reyes only interpreted songs written by other composers, now it is her versions that get interpreted in criollo venues and events, thus strengthening the legend of a voice on the edge of the delicacy and explosiveness of a trumpet.

Lucila Justina Sarcines Reyes was born on July 19, 1936, in the Rímac district. Lima, which had just mourned the death of composer Felipe Pinglo two months earlier, was a city on the verge of modernization that clung to its colonial and racist ways. Having been born black marked a difficult path in her life: after the father's premature death and a fire that left her and her 15 siblings homeless, she takes the streets to financially support her mother, and at 5 years old learns to sing in bars while begging for money in the port of Callao. After being admitted to a Franciscan convent and studying only until the third grade of primary school, now a teenager, she returns home, but suffers an attempt of rape by her new stepfather; she is forced to move to the central neighborhood of Barrios Altos, to live with her uncle, a guitarist from the legendary Guardia Vieja, also known as the founders of the Peruvian criollo waltz. This group of non-professional musicians, made up of bricklayers, merchants, artisans, marble workers and other employees, prolonged the oral traditions of their African slave ancestors in working-class neighborhoods of the capital. By the beginning of the 20th century, each mestizo neighborhood in Lima had its own style of criollo music, such as the panalivio from Malambo and the waltz and polka from La Victoria and Barrios Altos. With the arrival of the governments of Agustín B. Leguía, the construction of roads and an improvement in transport —plus the recent European influence that burst with radio and cinema—, the inter-neighborhood fusion of styles become possible and the city explodes in popular expressiveness. While the wealthy reject the music of their peons, which they associate with alcohol and disorder, it is the workers who listen carefully to the European waltzes and Aragonese jotas at the aristocratic halls, and later, back in their famous one-pipe alleys, transform their music under the spell of the night. It is in these sociability spaces that house numerous low-income families, where these criollos cheer up birthdays, weddings, anniversaries and other parties until dawn with the trill of their guitars and cajones.

It is there that Reyes, at 16 years old, picks up the legacy of the Guardia Vieja and her life changes forever: she is often asked to sing in jaranas (criollo parties), and since her voice stands out immediately, she is encouraged to make her debut on a radio show called "El Sentir de los Barrios", where she performs the waltz "Abandonada" by Sixto Carrera.

At 20 years old, she suddenly sees the opportunity to quit her dishwashing job in a criollo music club, but now she has two children to look after and, in addition, she has married a police officer who often hits her with his rubber stick and abuses her psychologically. So she runs away, not knowing that she also carries misfortune in her body: she suffers from emotional diabetes, edema and dyspnea —and not tuberculosis, as she is first diagnosed due of the red sputum she coughs out, giving rise to the myth that tuberculosis had deformed her vocal cords, leaving them better than before. She is admitted in the Bravo Chico hospital, where she stays for a year.

In 1960, after singing at the Felipe Pinglo Center, Lucha Reyes gets discovered by a talent scout and asked to join the Peña Ferrando, a group of criollo musicians and comedians who perform all over the country. Her job is to imitate famous singers of the time, such as Celia Cruz, Toña la Negra and Celina González, and this allows her to work on her body expression and develop the stage presence of a diva. Later, she joins the famous Peña Karamanduka of Piedad de la Jara, consolidating her career at a time criollo music was making a comeback. The music genre, which in 1944 was recognized by the Peruvian government as national music, was starting to be heard by the middle and upper classes, and its working class message was partially displaced by a nostalgic one that yearned for colonial times. Lucha Reyes’ most emblematic songs (chosen perhaps as an attempt to reflect her personal life) are about broken love, desolation and the difficult wait for a lover who will never return.

In 1970, Lucha Reyes records her first LP titled “La Morena de Oro del Perú” with label FTA (Associated Technical Manufacturers). With her hit “Regresa”, a composition by Augusto Polo Campos with arrangements by César Silva (who added the accordion intro that characterizes the song) and Álvaro Pérez, Pomada Lazón and Polo Bances on the guitar, cajon, and the saxophone, respectively, Lucha Reyes would win a Gold Record in 1971. Other songs on this LP that marked her career were "Tu Voz" by composer Juan Gonzalo Rose, "Qué importa" by Juan Mosto, "Aunque me odies" by Félix Figueroa and "Como una rosa roja", by Gladys María Pratz. All of these are included in this compilation.

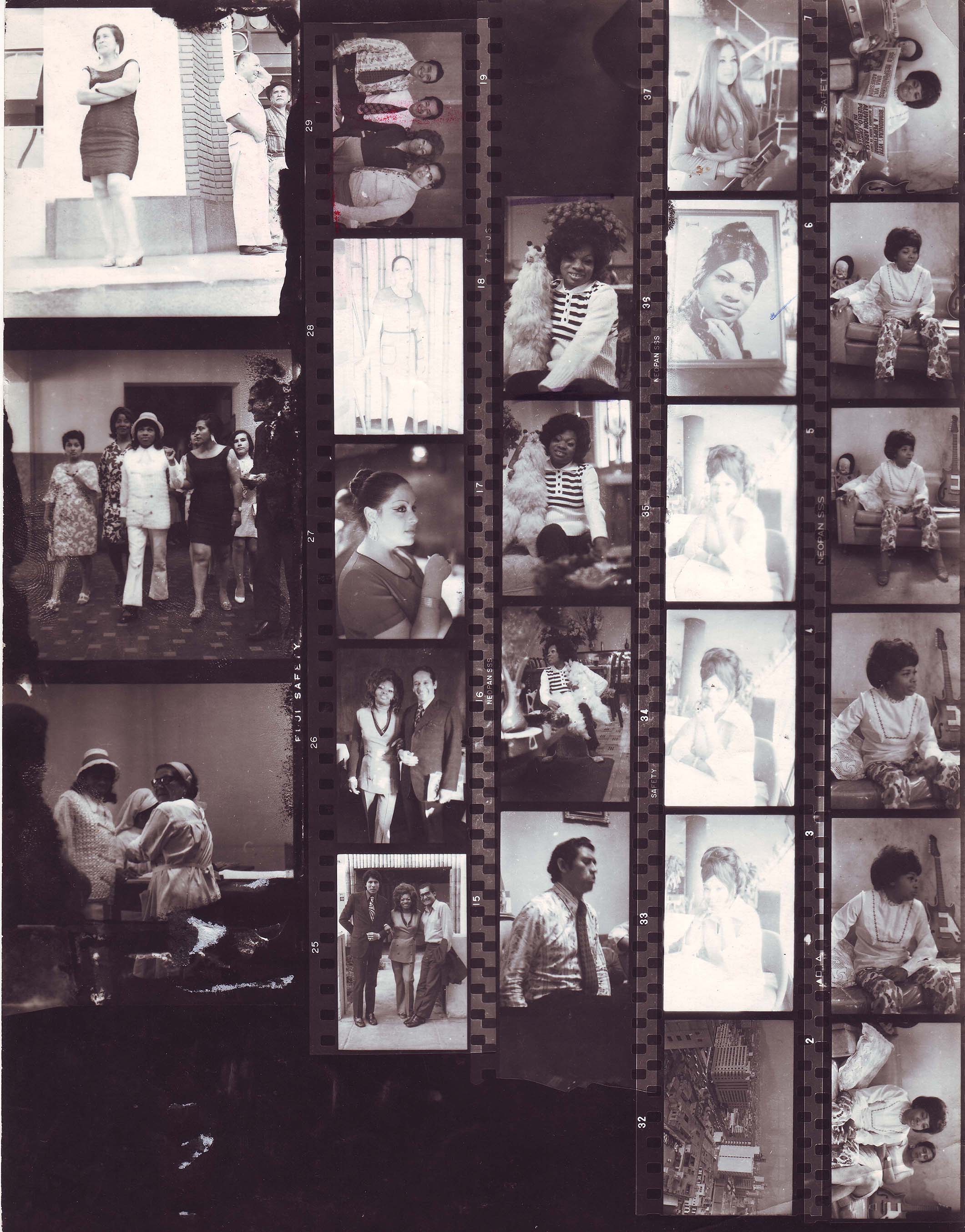

With her first LP out, her career takes off. The notoriety she receives leads her to relate with the wife of President Juan Velasco Alvarado, whose military and nationalist government supports the production and promotion of criollo music. Her days, perhaps far from the problems of childhood, get documented in television programs and photographs that always show her the same way: Lucha with her doll collection, Lucha with her pompous wigs, Lucha with her long dresses and her red lipstick in soft contrast with her ebony skin. Mostly in black and white, few in a faded color of the seventies, some photographs reveal intimate moments of her life: in one of them she is seen lying on a bed at the Bravo Chico hospital, where she was admitted again for high blood pressure and cardiovascular conditions in 1971. In the photo, she receives the affection of three people who stand outside of a window. She shakes their hands, guarded by a portrait of Sarita Colonia (the uncanonized saint of the working-class, thieves and murderers) placed at the head of her bed. Two boys look at her in amazement, as if they had just confirmed that her idol is not only real, but also black like them. Later, as told by her friends, she had to escape through a hospital window because she couldn’t afford another day of hospital stay.

Soon after, she resumes her career, and the following year, records her second LP titled "Una carta al cielo", with guitarist Rafael Amaranto. From that album, the songs included in this compilation are: "Una carta al cielo" by Salvador Oda, "Contigo y sin ti" by Augusto Polo Campos and "Jamás impediras" by Jose Escajadillo. Almost simultaneously, Lucha Reyes enters the radio as a host of a show titled “Primicias Criollas”. Her triumph in music comes at a time of Afro-Peruvian culture visibility in Peru and in the world, prompted, in part, and from the arts, by the siblings Nicomedes and Victoria Santa Cruz.

By 1973, Lucha Reyes had already reached the peak of her career, and that summer she gets invited to perform in Chicago and at the renowned Waldorf-Astoria in Manhattan. She still does not know that she will have to quit the stages forever that year, at the request of her doctors, who see her body deteriorating due to diabetes. But she now feels like an Ella Fitzgerald or a Nina Simone whose voice has acquired an unquestionable weight. Now she is listened to with respect and attention both in working-class alleys and in renowned theaters of the world.

Only when Lucha Reyes thinks she has all the strength to reach higher does her illness overcomes her, and she collapses on a wheelchair that her new partner, guitarist Ausberto Mendoza, helps push. A year before, she had released her third LP "Siempre Criolla" and now, sensing the end of her days, she records her fourth and last album titled "Mi última canción". In this compilation appear: "Soy tu amante" by Rafael Amaranto, "Tuya es mi vida" by Juan Mosto, and "Siempre te amaré" and "Mi última canción" by Pedro Pacheco, who writes the latter at her request, after she informs him about the unfortunate outcome she awaits. Her light shrinks with the speed with which she rose only three years earlier, and although she always sang sick, she must now cancel her contracts in order to rest because, in addition, she has become partially blind. Lucha Reyes feels that the marquees are going out on her, but her faith and her dolls keep her firm in the face of what may come, which comes, precisely, on Criollo Song Day, October 31, 1973, the day of the procession of the Lord of the Milagros, the black christ of which she was devoted. That morning, while heading to the procession, her arteries aged by diabetes surrender to a sudden heart attack and she dies, without ever imagining that the next day, the same mob of 30,000 of her fans who mourned her like a mater familias would be the ones to assault her hearse and remove her casket, without ever thinking that only women would carry her body for three hours until reaching the El Ángel cemetery, and without ever dreaming that from that date on, without the heat of her voice, Lima would be a ship that sails forever lost.

Manuel Jesus Orbegozo