Fuzz Killler Chicha

This compilation was originally released in 1982 under the title of Éxitos, éxitos, éxitos. It gathered some of the first recordings by Chacalon y La Nueva Crema that were released on 7-inch records between 1976 and 1981.

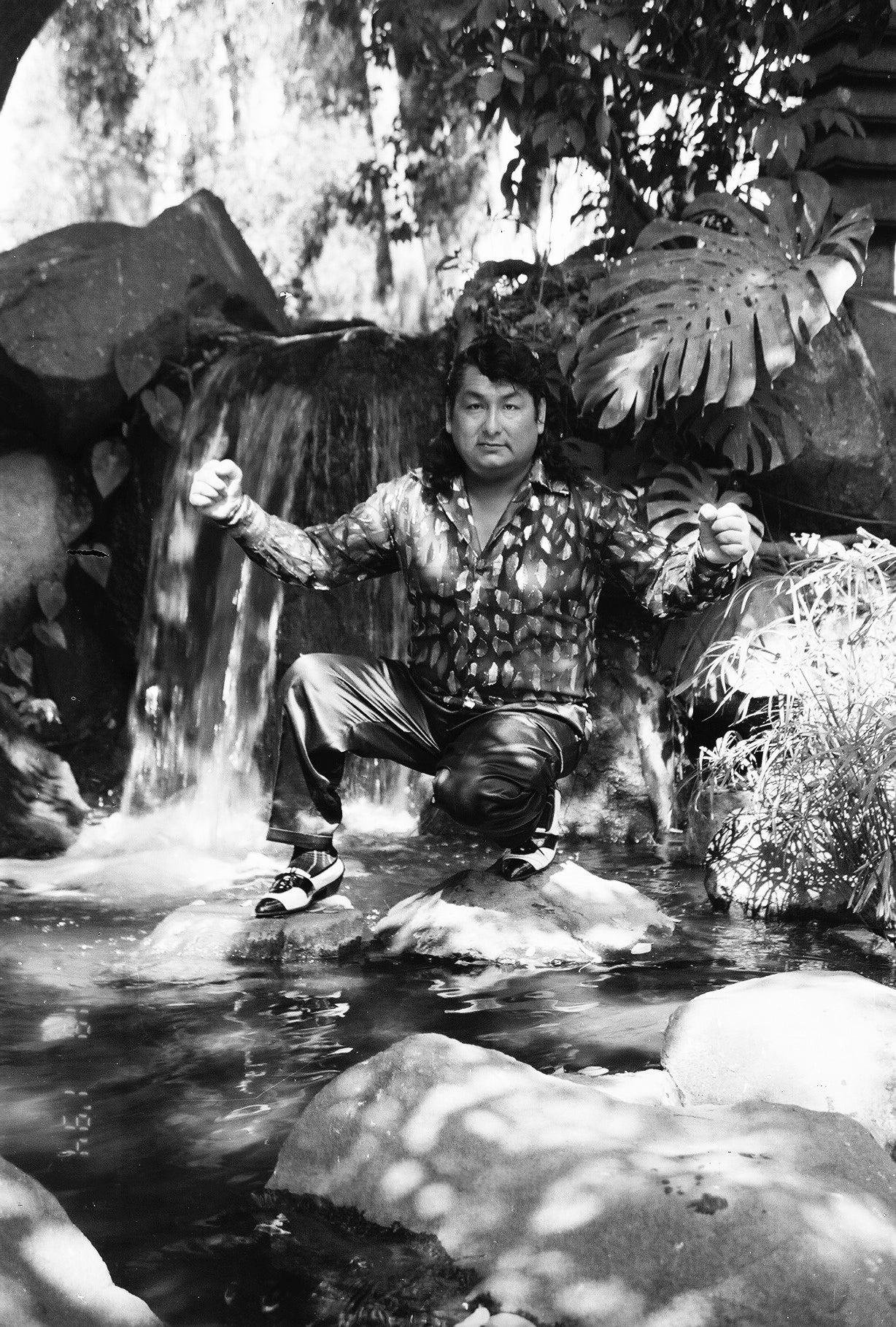

By the cover of the album, created from a photo quickly selected from anadult’s magazine and without the design work that characterized Discos Horoscopo’s stamp, we can deduce that it was a hurried edition, made to take advantage of the good reception that his previous LP, Chacalon y La Nueva Crema, had in 1981.

These twelve themes were written during the years of the de facto government of Francisco Morales Bermúdez. This dictatorship led Peru to an institutional and economic crisis that also affected major record labels, which opted to publish foreign musicians to insure sales.

The misgovernment, moreover, pushed a part of the Lima’s population into informal business practices on the streets, which went from offering second- hand clothes to used pianos, transforming the capital into a large market. This phenomenon of informal economy and poverty, later explained in several documentaries, could only be portrayed with songs that La Nueva Crema performed during those years.

THE PLACE

Located in the east of Lima, the district of La Victoria became, since 1945, an important economic center as a result of the creation of a wholesale market for agricultural products known as La Parada. More than one hundred thousand people and trucks arrived to La Parada daily from all over the country and gave life and color to it; many also began living there. Soon the area filled with hotels, bars, drug trafficking and prostitution.

These migrants turned into the new generation of Victorians who soon invaded the neighboring hills of El Pino and San Cosme, filling in a short time their boulders and alleyways with houses of several floors –reduced spaced that newcomers would sublet– and learning to live in gangland while forming neighborhood solidarity.

The district became a strategic place for musical projects. It had three coliseums, a long tradition of tropical musicians and a few bars where parishioners danced until dawn to fashionable bands playing live. It also housed record label debutantes (and pirate labels), whose cumbia and folklore vinyls were taken from their hands by the wholesalers —many times without covers— who would returning to their region with their trucks empty of agricultural products.

Numerous migrants, like the couple Lorenzo Palacios Huaypacusi and Olimpia Quispe, were attracted by this promising commercial activity, forming one of the many dysfunctional families relegated at the end of the occupational scale, with children who propped up the household economy by practicing passing occupations or picking up the more salvable of the spoiled vegetables and fruits that the merchants rejected. Lorenzo Palacios Quispe, their son, was one of these young folks. Growing up, Lorenzo had studied cosmetology and worked in shoemaking and tailoring. He was fan of professional wrestling and football. In his adolescence, he was imprisoned for hitting a guard.

His musical roots tied him to his family’s origins. Of his mother he assimilated the way of interpreting the huayno, and on his own he learned to touch the congas. Víctor Casahuamán, a successful music businessman, made him debut on vinyl as the singer of his Grupo Celeste in 1975, causing his interpretation of Viento to become a popular anthem. A couple of years after the name Chacalon was born, he left the band in search of economic improvements, playing in bands like Fruto Celeste, El Gran Fruto and El Super Grupo.

The charismatic singer lived a couple of blocks from the Mercado Mayorista, in an alley at the foot of Cerro San Cosme. It was in this alley called “El Bondy” where the composer and guitarist Jose Luis Carvallo and the owner of the then recent label Discos Horoscopo, Juan Campos, arrived in 1976 to propose Chacalon they get together to form a group called La Nueva Crema, in memory of the English band Cream.

Between national strikes and increasing political activity, both musicians recorded songs that, in future years, children much like Chacalon would sing on buses across the country in exchange for some coins.

THE SONGS

Ven mi amor, composed by Jose Luis Carballo, was the first song recorded by LaNueva Crema to feature Chacalón on the microphone. This golden record marked the group’s future line, sculpted with the accompaniment of Raul Barriga (guitar), Alberto Novoa «Piranha» (bass), Roberto Alberto Hinostrosa«Papita» (tomb), Valles «Kibe» (kettledrum) and Óscar «Chino» Siu (bongos), all of whom became studio musicians of the label from then on.

The Carballo-Palacios duo recorded eight songs between 1976 and 1978, five ofwhich appeared on this LP. These themes feature intense fuzztone and creativesolos that matched perfectly with the vocalist’s style. Once the duo came to an end, Carballo and the rest of musicians went on to form La Mermelada, while Chacalon recruited new members for his performances.

Soy provinciano is a composition by Juan Rebaza, a neighbor and friend of Chacalon, who was inspired by the early movement of the workers at La Parada. At first, the singer did not consider the song to be the band’s style. However, Soy provinciano immediately became an anthem for migrants and it was requested in every concert.

Poco a poco, a composition by Bolivian composers Orlando Rojas Rojas and Mauro Núñez, gain popularity at the end of the 70s and it was mostly heard in the folkloric clubs of Lima. Núñez was an exceptional diffuser of the charango and a friend of Moises Vivanco and mythical Yma Sumac. Chronologically, it was the latest recording on this LP, and its popularity led rival labels to copy the idea of versioning the song in cumbia.

Porque la quiero belongs to Lorenzo Palacios himself, who composed it after humming a melody to his musicians, according to his own testimony. The last four songs that end the album are creations of Augusto Loyola Castro’s, classics without the need for adjectives or major presentations: Dame tu amor, Ese amargo amor, Señor ten piedad de mí and La Paz y la dicha.

In total, twelve sobbing and heartfelt songs, interpreted in their own “achorada” and defiant way, consolidated Chacalon’s solo stage and won him the liking of the residents of La Parada (porters, domestic employees, interprovincial drivers) and the fervor of those marked by a “cruel destiny” (thieves and alcoholics without hope), who venerated him as the male version of the popular, yet uncanonized, saint Sarita Colonia.

THE LEGACY

Although Chacalon’s career experienced highs and lows after the release of this album, his intimate relationship with his audience remained, carried to levels as extreme as the ones he told Caretas magazine in July 1983:

“Once we were playing at a venue on Mexico Avenue, I was singing a song called “Llanto de un niño”, about a boy who was born in poverty, he has to leave his small town with his family. On the coast his father becomes a fisherman and dies, the son wants to send a letter to heaven. While I was singing, a guy who was there, at the front, pulled a switchblade and cut open his veins. He saved himself and then told me later that he had suffered a lot like the child in the song. Yes, the man had been drinking.”

Almost four decades after Éxitos, éxitos, éxitos, the very poor living conditions around La Parada have not improved substantially, despite the glorification of individual initiatives and the status of "small businesses" that the State conferred upon ambulatory trade in the late eighties.

Perhaps more popular organizations such as the Clubes de Madres, the Associations of Vaso de Leche and other collective acts were more successful; Chacalon unselfishly supported them from the beginning. He is also remembered for his free performances at many prisons in Lima. In 1987,

Chacalon was recognized by the UNESCO for his efforts to to make visible the problem of abandoned children in Peru.

The paternal image of the singer who imagines a place “where there is no Slavery”, has not been replaced in all these years, and songs such as La Paz y la dicha continue to summon the women and men who sing and dance for a free world.

Hugo Lévano G.