Jorge Chambergo's Legacy

To arrive in Lima in the 70s. The smog, the traffic, the chaos, the slums, the shacks. It is not the panorama of one; it is the experience of thousands of migrants staying at the edge of a man-eating capital. It is their struggle not to be devoured. Any attempt to understand the place and the present is immortalized in vinyl recordings: the music that refers to work, the highlands, the arrival to the capital, is revered among dust clouds lifted by their feet in motion, their fingers pointing to the sky. Happiness and misery are danced on the same night, on the same dance floor no one knows whether to laugh or cry. An outdated and conservative part of Lima despises them for this, but they go on. They exist.

Every era has a background music, an undisputed soundtrack. This is that of Andean migrants who arrive in Lima in the second half of the 20th century. Men and women who dance a mix of huayno with cumbia that spreads throughout the new city. The genre (misunderstood and mistreated, perhaps by association with the precariousness and informality of the time) stands out successfully on the periphery, sells millions of vinyl records, congregates thousands of faithful fans every day and even fills stadiums; later, two or three decades later, the new generations will chant the same songs in upper-middle class districts, after hearing the stories of their grandparents reflected in the lyrics. Perhaps one of the clearest examples of the rise of the ‘chicha’ phenomenon is that of Los Ovnis, the band recognized as the first to interpret Andean tropical music. 43 years after its foundation, we review their history and the origins of the genre.

Rock in the Mantaro Valley

The birth of tropical Andean music in the late 70s was not an impromptu act. Western influences had been entertaining the lives of young Peruvians for decades. The appearance of vinyl in the 60s, the American twist, the guaracha and the Colombian and Venezuelan cumbia that is heard in the 50s (Los Yepes, La Sonora Dinamita, Calixto Ochoa, among others), encourages young Peruvians to create music styles with their local components. The arrival of the electric guitar changes everything. Among the foundational names, we find musicians such as Carlos Baquerizo, Enrique Delgado and Tulio Enrique Leon. Shortly after, the same process would reach other regions of the country, forcing a change of landscape. In addition, the Andean migration to the capital encourages musical experimentation, cultural exchange and expressive needs.

Huancayo is the capital of the Junín region. It is located in the Mantaro Valley, in the central highlands of Peru, at 3,271 meters above sea level. In the mid-50s, the textile industry made this city the most important in central Peru, with its own migrants from nearby cities and rural communities (much like smaller version of Lima). The migration of families from Lima to Huancayo, as well as the construction of schools run by mestizo teachers, also from Lima, facilitated the arrival of Western influence. Cultural exchanges begin: a rock scene emerges where electric guitars and the western synthesizer replace traditional wind instruments. According to the anthropologist Fernando Ríos Correa in his essay “La chicha no es limeña. La música chicha como una variante de cumbia de los andes centrales del Perú”, these bands —made up of young university students, both from the periphery and from the center of Huancayo—, begin to play at local parties and festivities, where they are hired because promoters can’t afford to hire orchestras from Lima. At the public’s request, in one night they must interpret themes of cumbia, rock and new wave, and end the show with themes from

local music genres such as Santiago and Huaynos. The latter predominates and soon gets tropicalized. The first groups to approach this cumbia style are Los Demonios del Mantaro (who replace the rondín with the saxophone, an instrument heard in many Andean music genres) and Los Titanes de Juan de la Cruz, whose founder had lived in Huancayo.

In the second half of the 70s, the bands from this region begin to tour the central highlands, each time getting closer and closer to Lima, where a wave of Andean migrants start hiring them. Among those bands, one that has been incorporating the electric guitar in a tropical andean style stands out: Los Ovnis. Everything indicates that ‘chicha’ music arrived in Lima like another migrant from Huancayo.

Through the thousand traveled roads

In 1976, Jorge Chambergo is an anthropology student at the National University of the Center, in Huancayo. He listens carefully to the cumbia that comes from Lima, which local bands like Los Zetas de Chupaca (a group he sporadically plays guitar in) are responsible for disseminating throughout the city. At the same time, Chambergo, originally from Chupaca, a province southwest of Huancayo, admires Andean musicians such as Picaflor de Los Andes, Pastorita Huaracina and Flor Pucarina, who already sell out shows in coliseums of Lima. The appearance of Enrique Delgado and his electric guitar in his cumbia group Los Destellos —as well as bands like Los Yungas and Los Ilusionistas—, drives Chambergo to form a band with his brother Abelardo and other college classmates. As usual, they start by copying bands from Lima; soon they begin to play at Huancayo venues and surrounding communities, in matinees that go from 3 to 8pm. As for the name of the group, Chambergo recalls seeing a headline in a newspaper stand that said: "UFOs (OVNIS in spanish) kidnap a couple in Chile". As a premonition, a word that began to appear in the news countrywide caught his attention: invaders, strange unknown presences.

In 1978, Los Ovnis travel to Lima for the first time to record a 45 rpm album under Sonata label of the Zurita brothers. That year a friend tells them of a label that records cumbia bands from all over the country. After contacting their producer and director, Juan Campos Muñoz, the band signs with Discos Horoscopo and in 1978 they record more 45’ at Hafe studios, this time under the production of Pascual Saldarriaga, the mythical producer behind the distinctive sound of chicha music. It is in Hafe that they meet Lorenzo Palacios Quispe, "Chacalón", and his new band La Nueva Crema; they exchange tips and suggestions, becoming friends and simultaneously recording some of their most legendary songs: the same day that Chacalón and La Nueva Crema record their greatest hit Ven mi amor, Los Ovnis record theirs, Dime si.

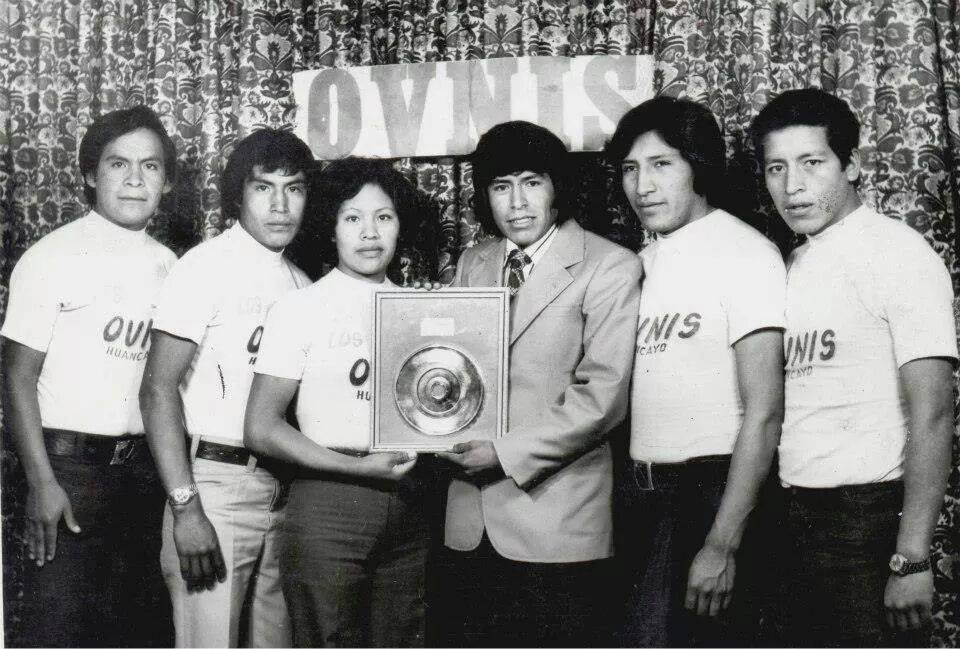

In 1979, after selling more than 100,000 copies with Dime si (sang by charismatic Julio Simeón, “Chapulín, El Dulce” of Los Shapis), Los Ovnis obtains a Gold Record from Juan Campos. Album orders begin to overwhelm the vinyl pressing machines that work day and night at this point, and sellers of the label are forced to spend the night in the factories if they want get their piece of records in order to fulfill the shipments to their respective regions.

Los Ovnis kick of the 80s by constantly traveling throughout the eastern Amazonian region. Many of the trips to inaccessible places are made in deplorable trucks, under the rain and indanger of accidents. At each stop, the villagers ask them to write song with styles of their regions, like ‘tahuampas’ and ‘pandillas’. In Juliaca, Puno, someone tells them about the Sikuris and they ask for the same thing: sir, make a song with that rhythm. They comply. In Lima, they get hired to perform at patronage festivals in venues located at the outskirts, and also at venues like Cream Rica, in the Surquillo district. Chambergo realizes that his songs manage to connect with migrants because something about them allows people to travel back home or bring out a beautiful or sad memory. He puts his anthropological training into practice, studies his surroundings, channels the feelings, and writes. No one in Los Ovnis imagines that soon their music will be recognized nationally, that it will be heard in cinemas throughout Peru. They only think about surviving from music long enough to start a business later on o perhaps finish their college education.

At the beginning of the 80s, Simeon leaves the group. In an attempt to cover the absence of the beloved vocalist, Chambergo recruits his nephew Wilmer Lazaro and Antonio ‘Toño’ Borja, the son of a university colleague, (another famed singer would also pass through their ranks, although briefly: José Abelardo Gutiérrez, known as ‘Tongo’). Both children are not older than 10 years of age. At the same time, while their music begins invading Lima, composers and musicians from the capital follow their steps and travel to Huancayo to form their tropical cumbia bands there. Some examples are Los Shapis and Vico y su Grupo Karicia.

In 1982, Chambergo and his band record their first LP, which has as cover art a drawing of small UFOs that attack a larger Star Wars spacecraft. It is titled Bailando con Los Ovnis (Dancing with UFOs).

Bailando con Los Ovnis

By 1982, Chambergo had been residing in Lima for a few years for work reasons. We have already stated that populations in the periphery of the capital identify with the band’s social message. However, everything related to their new tenants is viewed with contempt by the most conservative criollo sector. An example is Huayno music: before the ‘chicha’ boom, huayno did not have received an official radio spot after 6 in the morning. It was only possible to hear it at dawn. The listeners were, for the most part, truck drivers who picked up radio signal in the confines of the Peruvian territory. The panorama would change with new spaces dedicated to chicha in Radio Inca and Radio Unión, as well as the emergence of great musical promoters such as Marcahuasi, among other agents that helped spread the genre in all its variants.

The same thing happens with small labels, which in 1982, are no longer so small. Some decide to record longer albums, perhaps as an attempt to consolidate their artists. Los Ovnis turn comes with Bailando con Los Ovnis, a 12-song LP recorded in a single day. Once again at Hafe studios, producer Pascual Saldarriaga takes care of the magic touch.

The album is characterized by the experimentation with regional genres and the tropicalization of Bolivian themes, as is the case of Flor de Cochabamba.Corazon herido is born from the idea of incorporating the folklore of Juliaca, thus taking the mold of southern huayno. Valle del Canipaco is a purely Huancaino theme in reference to a valley in the region. Chofercito is a cumbia heavily influenced by Amazonian styles. Mi pobreza mi bonanza was composed to fit the ranges of vocalist Armando 'Armandito' Núñez, the oldest singer in the band, whose voice, according to Chambergo, did not fit the huayno style (in his words, “it is more elegant and northern than that of Simeon”). Mi Cuzco is a folklore theme alluding to the imperial city that Chambergo would often visit at the time with the intention of tropicalizing traditional sounds of the region.

The most special, the rara avis, is perhaps Olvido, a poem with music composed by Chambergo. The lyrics were written by Carlos Arroyo, a university student and poet who had given his poems to Chambergo so that he would use one of them in one of his songs (Olvido became the most requested in villages of the jungle, since Arroyo, now a teacher, had spread his poems throughout the region years before; it was common to hear hundreds of students recite the poem at concerts). It is the only cumbia in spoken word known until that date. Te arrepentirás has resembles the sound of Pintura Roja, a group that was close to making its debut at the time. There is also Mala mujer and Linda huancaína, a tribute song to Huancayo.

Chambergo recalls recording his parts with an Ibanez and a rental stratocaster at times. We hear the prolonged sound of the delay on the first guitar and the clean vibrations of a Schaller wah-wah pedal on the rhythm.

Recorded before the arrival of ‘the kids’ (Borja and Lázaro), the other voice we hear is that of Simeon, "Chapulín, El Dulce". His great ability to transmit emotions is heard on songs like Linda colegiala and Corazón herido.It is a voice linked to the Andean feeling, with the particular crying-like pitch of huayno singers. However, at the time of the recording, Simeon was no longer part of the Los Ovnis, which means that the tracks he performs in belong to early 45’ recordings. Finally, in the song Tarde te arrepentirás, we hear the voice of singer Enma Verástegui along with that of Núñez.

The musicians who participated in the recording of Bailando con Los Ovnis, as well as in the songs collected from earlier 45s’ that were included in the album, are:

Jorge Chambergo (lead guitar)

Abelardo Chambergo (rhythm guitar) Alfredo Verano (bongo)

Silvio Quispe ‘Pirula’ (kettledrum)

Alberto Mallque (conga)

Enma Verástegui (vocals)

Julio Simeón, ‘Chapulín, El Dulce’ (vocals) Armando Nuñez, ‘Armandito’ (vocals)

The galactic sound of Los Ovnis

After the first LP got published, the Los Ovnis went to record six more under Discos Horoscopo, perfecting the 'chicha' sound with the support of the longed 'mafia', a group of session musicians made up by Ricardo Hinostroza 'Papita' and Ricardo Valles, 'Kibe', among other legends of Peruvian cumbia. As a response to 'El Alisal' by Mina Gonzales and Totito de Santa Cruz, Chambergo composes a similar tune but in ‘chicha’ a month before Los Shapis publish their first 45 ', that included their best known topic to date: El Aguajal, a remake of Gonzales’s hit. It is then that Chambergo makes the decision to break up with Discos Horoscopo, although a few years later, he would return under the advice of who was his great friend, Chacalón. Los Ovnis would go on to launch an LP per year on average.

Then would come the international tours, along with times of terrorism and corpses on the roads, one of the worst hyperinflations in Latin America, misery and hunger. In music, they receive an opportunity that no other 'chicha' band had had until then: they get hired by the film company Grupo Chaski to musicalize Gregorio, a feature film about a child who travels from the Andes to the capital and experiences cultural shock while facing the hardest side of the city. This nationwide exhibition of their music opens the doors to the north side of the country, where tropical Andean music had not yet hit. Chambergo's lyrics take on a marked social approach, some in reference to the difficulties of Peruvian miners and the lives of migrant college students in Lima, as well as children abandoned by their fathers. At the end of the 90s, the band changed its name to Los Galacticos Ovnis, reinventing its image with new members, but soon after they would return to their origins, the original name and to play their best known songs.

For Los Ovnis, a 43-year-old artistic career that is not over yet, begins with this LP that we rediscover today. We celebrate the founders of Andean tropical music by listening to their first album remastered, a magnum opus that, like all classics, has managed to endure in the history of Peruvian music.