The Working Class Myth

Lorenzo Palacios Quispe "Chacalón" is a myth. More than a musical star, he is both a religious and secular phenomenon for the masses. Every year on his birthday, his tomb becomes a place of fevered pilgrimage where devotees pray, make wishes and ask for miracles, all done over songs, cases of beer, dancing and toasting. In Peru, his figure and music erases the distance between the holy and the profane, the hero and the lumpen. Chacalón is, for many Peruvians, the people’s angel, the messiah of the poor, the marginalized ‘Inkarri'.

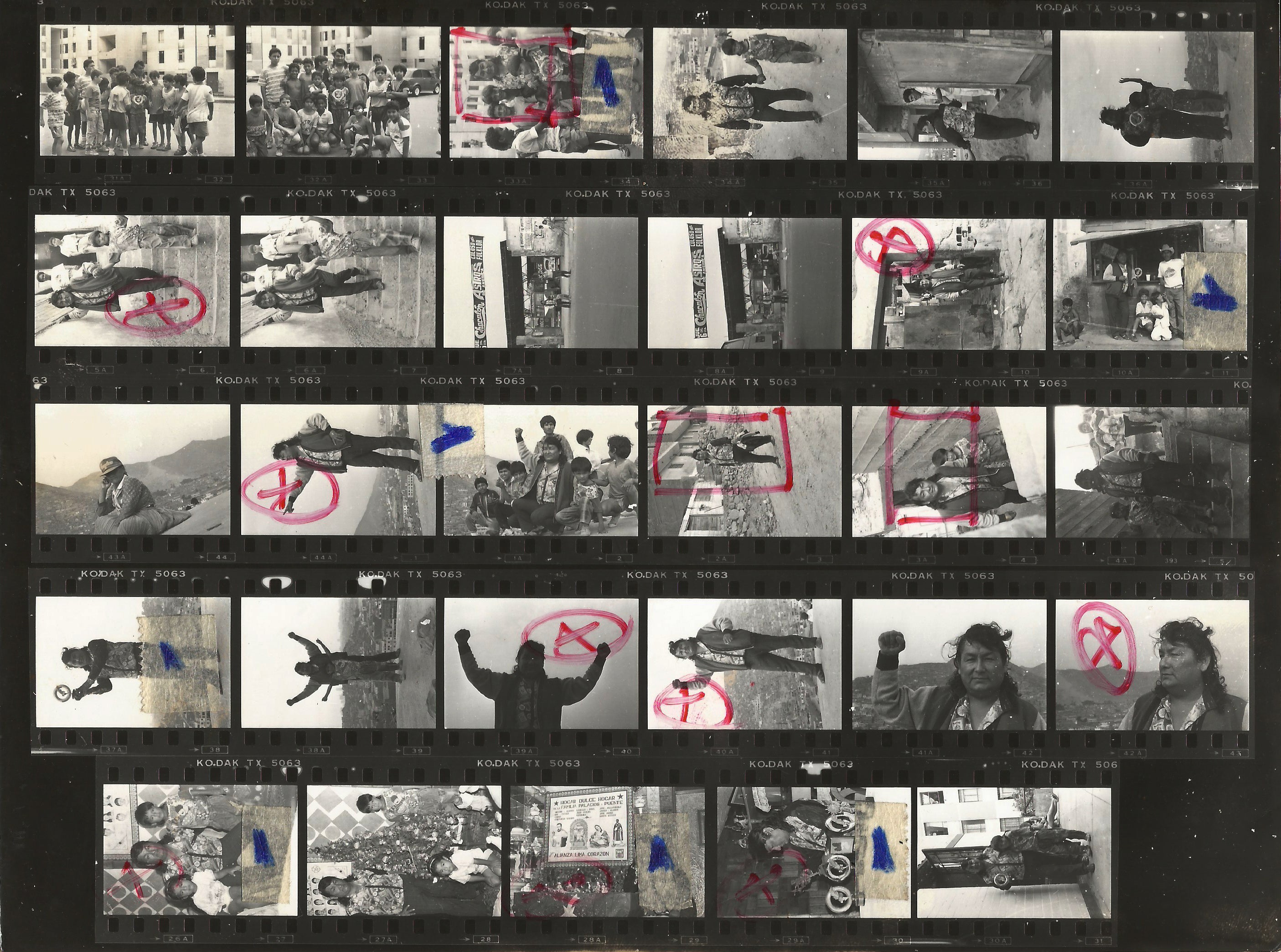

"When Chacalón sings, the hills come down”, was one of his favorite phrases and with it he referred to the migrant masses that invaded the hills and beaches that surround Lima like a "ring of fire" (José María Arguedas dixit). It was the early 80s and while bombs and a dirty war exploded in the Andes, in Lima, the new and ever-growing population of migrants “climbed down" from their precarious homes and filled venues to dance "chicha" music and to celebrate who they saw as their redeemer.

Despite being a model messianic figure, Lorenzo Palacios had very humble origins. The son of a music dancer from Huancayo and a singer of huayno music (Andean folk) from Ayacucho, Chacalón was born in Lima in 1950. As a teen, he had his debut on stage as the singer of huayno band "The Indios Quechuas". The main requirement to sing that genre of music was to have a powerful ribcage and young Lorenzo seemed to have the needed lung capacity for “guapeos”, thunderous voice blows that the genre required.

Simultaneously, in the late 50s, Lorenzo’s neighborhood “Bondy" located in the heart El Augustino district, was full of tropical music fans. Cuban son and guaracha music were fashionable genres at the time and in the mid-60s, Tropicalia began to intermingle with Colombian cumbia, conquering the radio soon after. A pioneering band of this hybridity was Riparian (whose members lived in Lorenzo’s neighborhood). They became one of the first Peruvian tropical music bands to be seen as a mix between cumbia and chicha. Their music genre is still being disputed.

But Chacalón preferred to call himself a “chichero”, or someone who plays chicha music. The word comes from “chicha", a Peruvian term with different cultural connotations that refers to past and present history: from the holy Incan drink made from fermented corn to a new musical style, a way of living in the world, a new migrant culture in Lima. “Chicha” alludes to population disorder and overflowing, to drunkenness and chaos, but it’s also seen as a way of appropriating and making fun of the West; for some “chicha” alludes to the "poorly done”, for others it’s a mean of expression that transgresses the rules of "good taste" to create something totally new. "Neither a replica or a copy, but a heroic creation”, the indomarxist Jose Carlos Mariátegui would say.

Chicha music is neither a replica or a copy, despite using Western instruments, such as the electric guitar, bass, drums and organs, and mixing them with cymbals, congas and tropical Guiros. Chicha music has indomestizo elements (like Huayno music) tucked deep in his blood. Listen to the powerful cries of Chacalón and you will hear the heartfelt music of Huancayo; listen to his delicate voice breaks and you will hear the sweet music of Ayacucho. The mix of delicacy and strength and rural and cosmopolitan elements, is part of the secret of seduction that chicha music has had over the masses.

Aside from use of electric instruments, rock music has influenced chicha music in other ways. Chacalón’s band was called New Cream as a tribute to the British band Cream. Their use of powerful fuzz tones and wah wah pedals for acid riffs and catchy solos, are the echoes of a rebellious music that wanted to silence the noises of a marginalized and exploitative city atmosphere debased by the most savage capitalism. "I seek a new life in this city / where everything is money and there is evil", reads “Provinciano”, Chacalón’s most famous songs.

It’s because lyrics like these that people saw Chacalón as a messianic figure who sang about the promise of a new life. He sang about pain, alcohol and betrayal, but also about solidarity, love and hope. Chacalón sang to the most marginalized part of society, the lumpenproletariat, and not the middle class or the wealthy. Lorenzo Palacios did not see differences between those who complied with the law or those who transgressed it, because in marginality, survival is the only rule and the boundaries between good and evil become very subtle. "Eat first, then morals”, said Chacalón.

This is why Chacalón got his mythical status more than any other figure in Peruvian popular music culture. Chacalón continues to resound in the heart of the desperate and those struggling against an unjust system, among workers and among those who no longer have work or a home. But this is not just a Latin American problem; the “first world" also lives a false splendor and has its own marginalized and desperate. Perhaps Chacalón now sings to them too.

And if we all look for the same things in life, perhaps we will all find love and happiness, peace and joy, celebration and work, or as Lorenzo Palacios would say: Chamba and Vacilón (work and a good time).

Alfredo Villar