Revolutionizing Tropical Music: The Legacy of Los Diablos Rojos

There was a time when the city of Lima had almost no Anglo-Saxon influence. Its musical identity was expressed through fine waltzes and other rhythms that characterized música criolla (Peruvian creole music). Before the great migration from the Peruvian Andes to the capital – which, in addition to the confluence of cultures, gave way to the combination of different genres that already existed and others that were invented thanks to talented musicians from other regions of the country – in Lima, music was born every night in traditional music venues called peñas.

It all began in the Peña Criolla Cañete Chico. Located in Lima's Magdalena del Mar neighborhood, it was one of many in the city where the most talented criollo artists of the time met, as well as other more amateur musicians who listened to the masters of the genre, learned from afar, and fantasized about getting on stage and being the ones to entertain everyone. Guitars in hand, vocal cords in tune, and searching for balance on the Peruvian cajón, these musicians prepared for what was sure to be a long night. The peña had no closing times, they could play as long as they wanted. There was no shortage of improvisation and pisco. In fact, both were party vitamins. A good gastronomic spice could not be missing either. Being Criollo also meant being bohemian, hedonistic and experiencing music as a whole.

Música criolla was founded in Peru in the second half of the 20th century and represented the entire Peruvian music industry at the time. There was a huge boom in singers and composers, and the demand grew exponentially. Its popularity was so great that radio stations began broadcasting música criolla songs, while the recording of records accelerated. Names like Augusto Polo Campos, Carmencita Lara, Lucha Reyes or Arturo "Zambo" Cavero, now known worldwide, began to become popular in the sixties and seventies. As more artists emerged, more records were made and instrumentalists were needed to accompany them.

The year was 1966. Marino Valencia Garay was 22 years old and had been playing the guitar for eight years. His young age did not diminish his talent. As an avid participant in jaranas, the traditional gatherings where música criolla was played, he had already reached a privileged place as a listener and as a musician. Marino had grown up listening to The Ventures, his greatest source of inspiration, and La Sonora Matancera. English-language rock 'n' roll and Cuban son converged in the mind of a boy who visited those peñas to accompany with his guitar skills renowned musicians like Luis Abanto Morales. Fridays and Saturdays were reserved for them and the best boleristas of the time, such as Pedrito Otiniano and Jhonny Farfán.

Música criolla became the incubator of Marino's unique ability at his young age. In Cañete Chico, a project began to take shape that would transcend the history of the Peruvian music industry as well as the criollo genre of the time. The owner of the peña had already taken a liking to Marino and offered him a space to rehearse with his own band, which, although still in its infancy, would break the sales records of Sonoradio, the most important record label of the time, recognized worldwide for its luxurious catalog that included Óscar Avilés, Fiesta Criolla, Gustavo Hit Moreno, Los Yungas, and many others.

The Peruvian cumbia band Los Diablos Rojos was born within the quincha and adobe walls of Cañete Chico with a proposal very different from what all the musicians of the time were working on: an instrumental tropical music style of their own. Even Enrique Delgado (Los Destellos), Beto Cuesta (Los Ecos) and Berardo Hernandez (Manzanita y su Conjunto), who all found a source of income in música criolla, did not limit themselves to working for hire. They were all crossing the same bridge, the bridge of tropical music. Above all, the sense of renewal was the incentive for this bet. If they wanted to change the paradigm, they would not do it by copying styles they had already heard many times before.

Between 1968 and 1970, there were orchestras in Peru playing pasodoble, tango, and foreign rhythms that these musicians no longer identified with. The references would always be there, but it was time to invent something new, local and their own. The interesting thing about the peñas is that they were a one-way ticket to the record labels, and in the case of Valencia, it was no different. All his work paid off and he was hired as a musical director at Rey Records. As word of his talent spread, his colleagues at Sonoradio convinced him to join the label as a staff musician, which meant recording with the label’s signed artists. Valencia went on to record with some of the most important artists of the time, such as Los Trovadores del Norte and Jesús Vásquez.

That was when the Argentinean Enrique Lynch, the talented musical director of Sonoradio, had a hunch. Without knowing the other members of the band, and only from what he had heard of Valencia, which was little, but very positive, he proposed to him to record an album. The band's first 45 r.p.m., which included “El Chacarero” and “El Fanfarrón”, sold 100,000 copies, an unprecedented success for a label founded almost twenty years earlier. Marino Valencia still remembers the number of the record: "13125". It was, he says, his musical birth certificate. Only two years earlier, in 1968, Enrique Delgado of Los Destellos had initiated this phenomenon of renewal of tropical instrumental music with "El avispón". In fact, it was the director of the famous cumbia band who encouraged Valencia to abandon the criollo genre and embrace tropical music. After the success of the first 45 rpm of Los Diablos Rojos, all the musicians who were in this transition, some closer than others, took this direction.

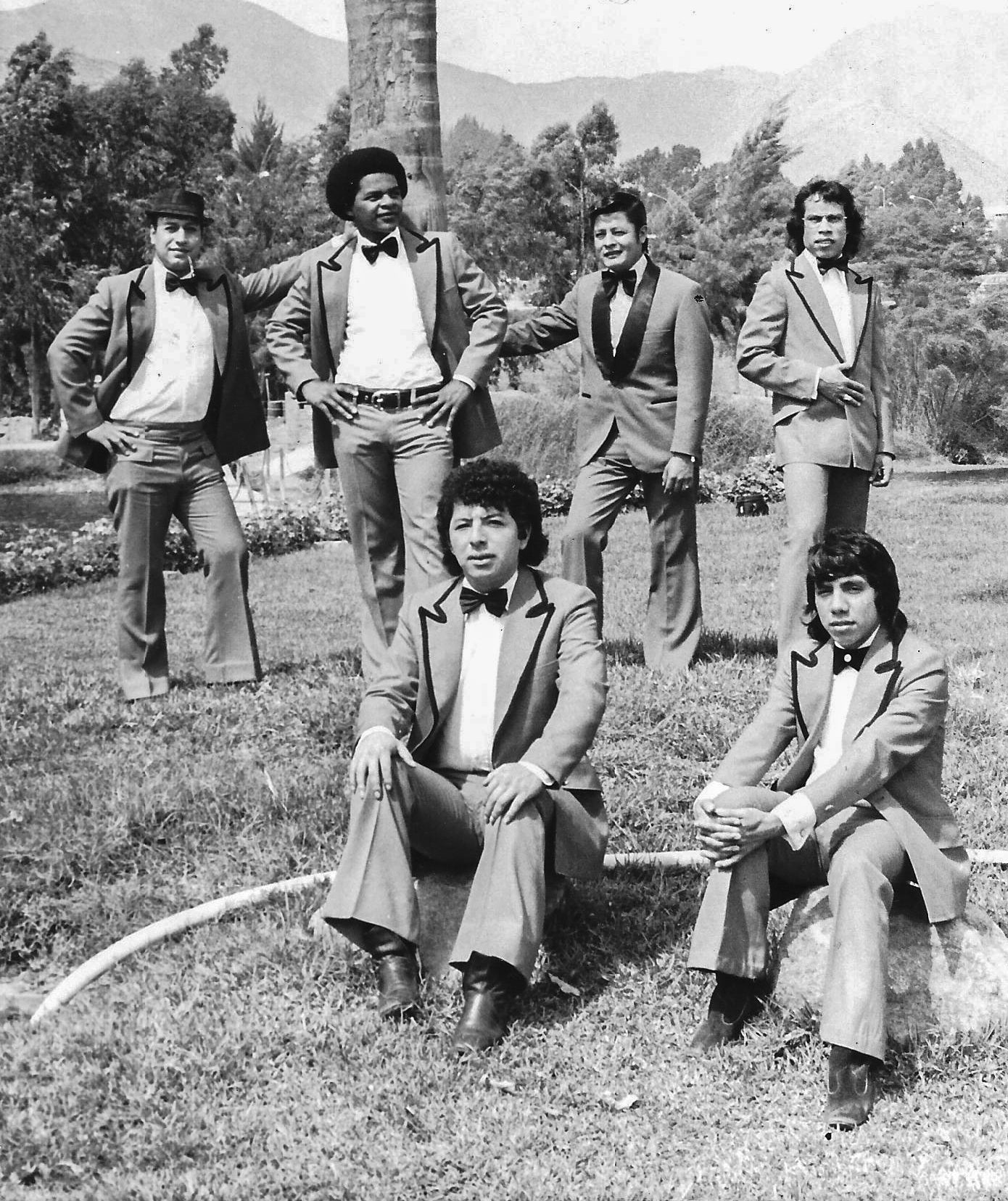

Los Diablos Rojos was formed by Víctor 'Cucho' Gómez Rosales on bass, Raúl Quiñonez on timbales, David Bravo Napán on drums, Luis Carrillo on vocals and Marino Valencia. That 45 rpm was the beginning of a great musical project that would go on to produce four LPs of instrumental music over the course of four years: “Al rojo vivo”, “Paseo Tropical”, “Vuelo Tropical” and “Los triunfadores”, released between 1970 and 1974. The best and most representative songs of that era make up this compilation, edited with the care and dedication that characterizes Discos Fantástico!, faithful to its work of rescuing and revaluing Latin American music.

With thirty studio albums and gold records to their credit, there are three important reasons that have contributed to the longevity of Los Diablos Rojos over time: discipline, fidelity to originality, and perseverance on the road. Creating their own style that could be recognized from afar was their main idea from the beginning. And they succeeded. Musicians, according to Valencia, had to be inventors and architects. It is undeniable that all the creations are linked to different musical references around the world, and this enriches the offer, as long as there is the capacity to reinvent and propose. Who would have thought that tropical music would have the explosive characteristics of an electric guitar, with a sound that could be recognized in bands from other continents? The limits could only be set by musical criteria and not by preconceived ideas or previous proposals.

Today, Los Diablos Rojos are known around the world for a unique tropical sound that has transcended passing fashions and managed to hold its own in an era marked by transience and oblivion. Thanks to their ability to take risks, the band has been able to create a new musical genre, mixing rhythms and sounds unimaginable to previous generations. Over the years, they have become the forerunners of a trend that has been developing for half a century and is gaining more and more praise and recognition. They have become a musical reference for other contemporary tropical music bands that have found in Los Diablos Rojos, above all, an example of creativity and resilience.

Ailen Pérez B.